Zoom Lens or Prime? 15/18/21mm Lenses

Related: digital sensor, Eastern Sierra, external articles by Lloyd, focusing, ghosting flare, How-To, lens flare, Live View, longitudinal chromatic aberration, Lundy Canyon area, optics, peak bagging, secondary longitudinal chromatic aberration, veiling flare, visual impact, Zeiss, Zeiss 15mm f/2.8 Distagon, Zeiss 18mm f/2.8, Zeiss 21mm f/2.8 Distagon, Zeiss Distagon, ZEISS Lenspire, Zeiss Milvus, zoom

by Lloyd Chambers, diglloyd.com

As of 2017, Zeiss offers 3 lines of DSLR lenses for Canon and Nikon DSLRs: (1) the original ZF.2/ZE line, for those lenses not yet available in Milvus design, (2) the Milvus ZF.2 / ZE line, (3) the reference-standard Otus line.

See ZEISS Fills Out the Milvus DSLR Lens Lineup with the 2.8/21, 2/35, 2/50M, 2/100M and other related articles as well as Harnessing Wide Angle Lenses: Perspective and Impact.

This is the first article of a multi-part series discussing Zeiss DSLR prime lenses against the best native zooms, starting with the ultra wide angle range (15mm, 18mm, 21mm). While the scope of the examples in this series is confined to DSLR lenses for Canon and Nikon, the same general considerations apply to lenses for mirrorless cameras.

Prime lens = lens having a fixed focal length and thus fixed angle of view, e.g., 50mm or 24mm.

Zoom lens* = lens having a continuous range of focal lengths and angle of view, e.g., 11-24mm or 16-35mm.

The goal of this series is to establish a conceptual framework by which one evaluates a “prime or zoom” choice for one’s own work. Accordingly, this is not a comparative lens review. In particular, I avoid “naming names” because the goal is not a lens review (comparing even two lenses is very challenging and lengthy to do well) but mainly because understanding and prioritizing for oneself which lens characteristics are most important is knowledge that remains useful no matter how many new lenses emerge.

* A true zoom lens is a parfocal lens, one that maintains focus as the focal length is changed. These are rare in the consumer and pro still-photography markets but high-end cine lenses are usually parfocal. Nearly all still photography lenses are varifocal lenses; the lens must be refocused after zooming. It’s easy enough to check: go to 10X Live View or so, focus, then zoom the lens. Most all zooms then go wildly out of focus.

Prime vs Zoom (general)

As the first articles in the series, general “prime vs zoom” considerations are covered here before moving on to specific lens behaviors for the 15/18/21mm range.

Until fairly recently, zoom lenses were undesirable when peak image quality was the goal; for maximum image quality, the prime lens was ruled the roost. But starting around 2014 some impressive zoom lenses began to appear, begging the question of whether prime lenses might no longer be necessary. A pro-grade zoom is entirely sufficient for many purposes, being indispensable in shooting situations with restricted movement and/or where fast-changing subject require the quickness of a zoom and/or where there are no available prime lens choices and/or where changing lenses too often means dust on the sensor.

The appeal of the zoom is why a prime lens is rarely bundled with a camera and why very few fixed-lens entry-level cameras use a prime lens. Yet ironically the most ubiquitous cameras use a prime lens: camera phones. The iPhone 7 Plus even uses dual prime lenses. Perhaps the DSLR and mirrorless camera vendors might ultimately adjust their offerings as this “prime lens training effect” takes hold?

Zooms can be an advantage, or an impediment

Most any camera buyer will gravitate immediately to the zoom—a zoom seems so much more appealing for its versatility, because it is. However, the assumption is that versatility is always a plus, which it is not.

Zoom lenses are hard to use, that is, hard to use well. An advanced photographer can put a zoom lens to appropriate use, whereas inexperienced photographers are too-often induced to plant both feet and zoom the lens instead of using “foot zoom”—choosing the distance to the subject by conscious thought. By shooting using a prime lens, an appreciation of perspective is gained more rapidly. Moving position changes the photographic perspective, which is a function of distance to the subject. Thus a prime lens is a better choice for learning photographic composition. See 24 photo tips: Shoot One Lens, and Not a Zoom as well as Harnessing Wide Angle Lenses: Perspective and Impact.

Taking myself as an example: decades ago, I started out with 50mm/55mm primes on film cameras, then primes on 4X5 and 6X7 and 6X17 formats. With the arrival of digital DSLRs, I found that I invariably made my best images with prime lenses, not zooms. The optical superiority of the prime lens was definitely a factor for technical image quality, but my compositions turned out better with a prime lens. My retrospective conclusion is that a prime lens seems to make me think more carefully about the image I was making.

So... why use a prime lens?

Prime lenses retain key advantages for the discerning photographer looking for an optimized solution, the optimizations being both physical (size and weight, high quality manual focus) and of course total optical quality across a very wide shooting envelope. Advantages can also include distortion and faster aperture, though the latter two do not always hold true.

A response from an optical expert at Zeiss in an email conversation has stuck in my mind over the years in reference to my “is it this or that” persistent questioning: “It is the sum of everything”. That is the crux of the matter when choosing a lens, and it is why I consider field shooting real images to be the proper way to evaluate a lens (not lab tests, which miss all sorts of important behaviors).

To say that lens performance is a sum total of many optical behaviors is to say that each optical design has strengths and weakness, all traded off / balance against each other. Since a prime lens can be optimized for a single focal length, it has greater potential for fewer weaknesses and more strengths—a “sum” that is generally superior to what any zoom can achieve (at least at similar cost). Any particular optical aspect might not be superior, but it is the final image that matters, the total result. A lens that delivers a consistently high sum total performance across its focusing range and myriad lighting challenges is a lens one can count on, every time.

Composition of the “sum” that adds up to the final image:

- Image quality: superior contrast and sharpness and flare control, often lower distortion.

- Control over color aberrations, particularly in difficult lighting, like blue/violet mountain light.

- More pleasing overall rendering style, particularly with longer focal lengths.

- Focus shift and field curvature are usually much better controlled with a prime lens.

- Lens speed; brighter image, particularly at medium and longer focal lengths.

- Lifespan and durability: fewer moving parts, less to go out of alignment, particularly with manual focus helicoid-based lenses like Zeiss Milvus and Zeiss Otus.

- Focus stacking: precise control over focus bracketing, including accurate distance scale.

- Focusing “throw” and feel and often a convenient hard infinity stop.

- Size and weight, ability to use filters.

- Encourages the photographer to think through the appropriate shooting distance / perspective.

Image quality influences

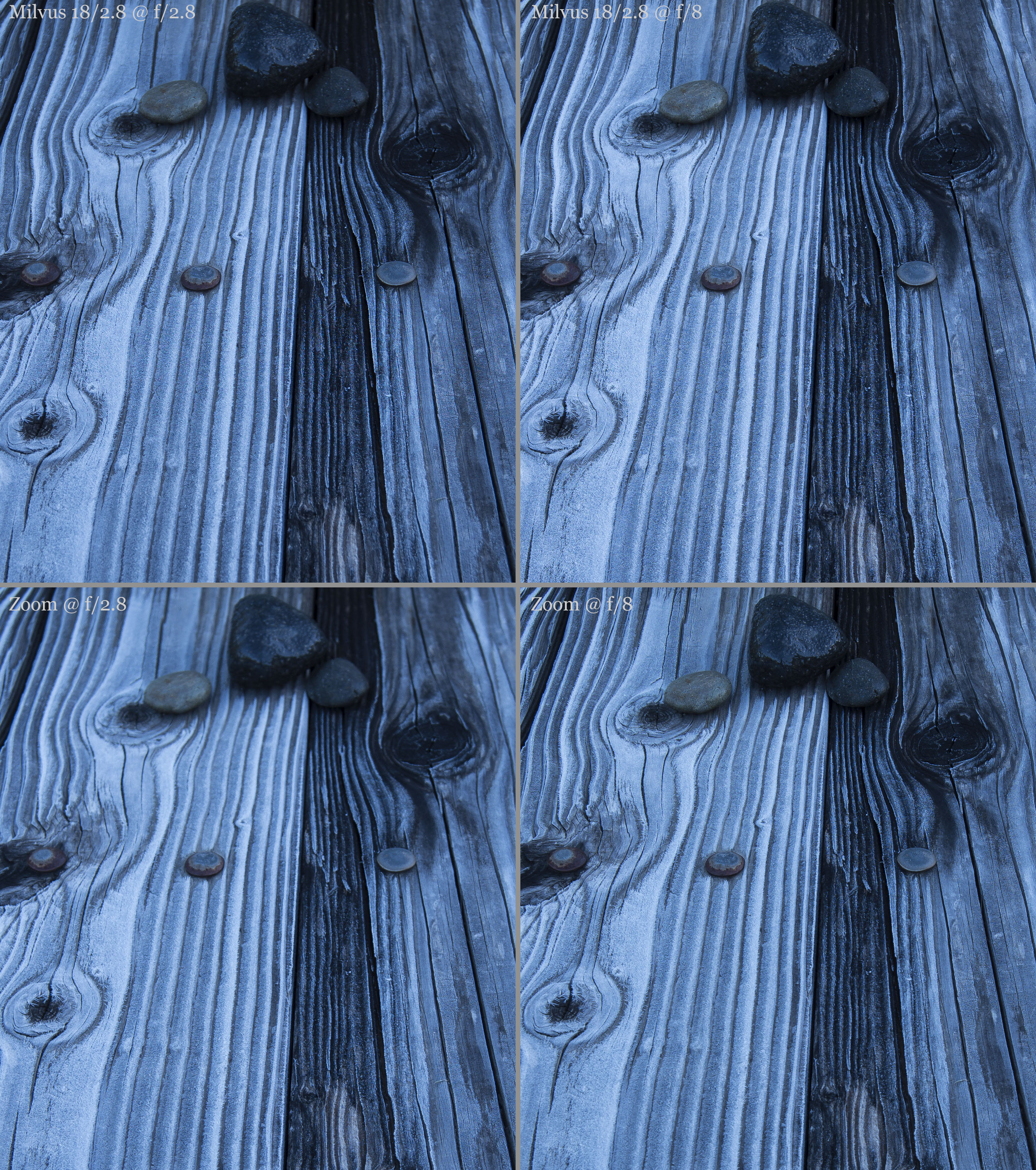

The examples here pit the very best zooms against Zeiss Milvus primes—best against best. No “kit zooms” or 2nd-level prosumer lenses were used.

The examples are chosen to show representative aspects of zoom versus prime for key image quality issues. The emphasis is NOT on sharpness, because the very best DSLR zooms are in fact very sharp. Refer to the “sum total” discussion above.

Because web size images (even fairly large) cannot show much in the way of details from a 36 or 50 megapixel camera, crops are used to illustrate the differences, using suitable subject matter. Be sure to view all image at full resolution (click).

Color correction, especially for blue light

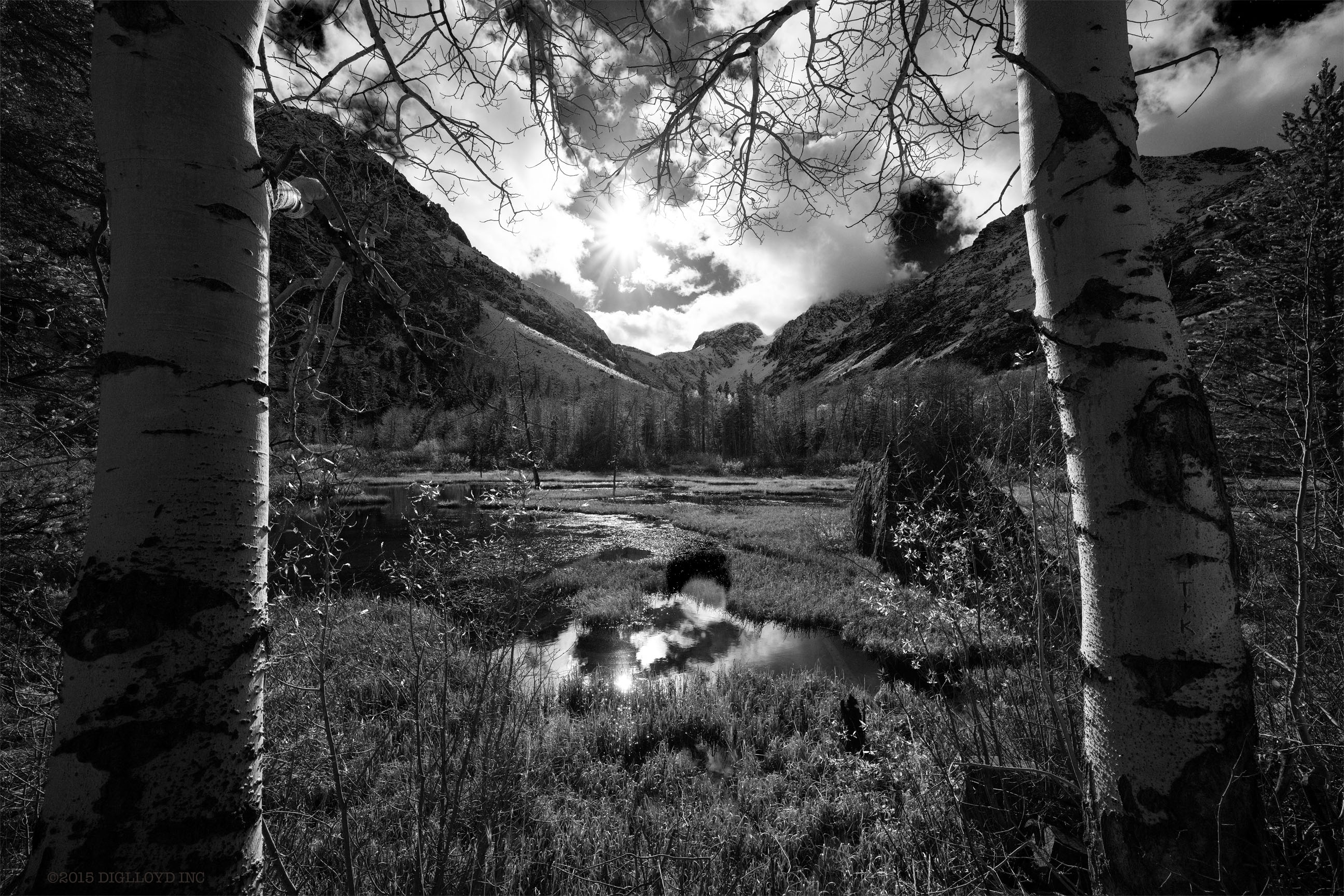

Many types of color errors exist in optical designs, but I often shoot in the mountains at dusk where lighting can be extremely blue, with a color temperature of up to 25,000°K, as shown in the Lundy Canyon Beaver Pond At Dusk image. Optical performance under such conditions can stray quite a bit from what lab tests claim for a lens.

Optically, the violet/blue end of the spectrum is the most difficult to correct, being the source of the dreaded “purple fringing” (really violet/blue fringing). Even with well corrected lenses, the blue end of the spectrum can subtly “bloom” around fine details, depriving the image of brilliance (micro contrast). This is so even though most digital sensors having a hard cut-filter at about 420nm.

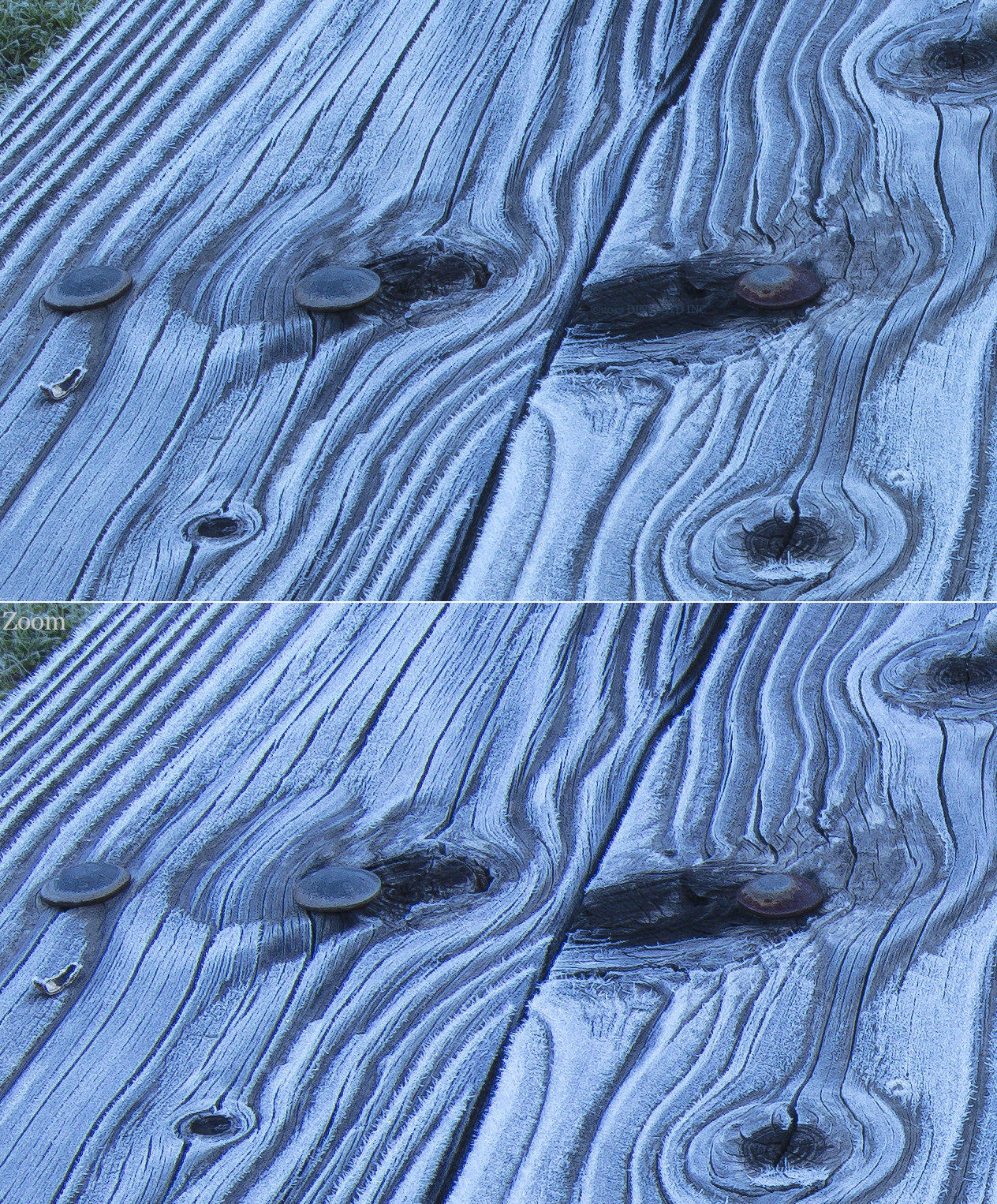

In the frosty comparison crops that follow below, the light is considerably warmer in color temperature (perhaps 6500°K), so it is far from the most challenging case as is seen in the Lundy Canyon image below it.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Milvus 18mm f/2.8

[low-res image for bot]

Blue light like this mountain canyon at dusk places a premium on color correction.

Canon EOS 5DS R + Zeiss Distagon T* 2.8/21 ZE @ 21mm

[low-res image for bot]

Below, the Zeiss Milvus 15mm f/2.8 is compared here on the 50-megapixel Canon 5Ds R, whose sensor is demanding as it gets—fitting given the high performance lenses used here. The zoom stands with the very best that Canon has to offer, and yet its image shows violet haloes along all the high contrast edges (most obvious along dark cracks). The Milvus has crisp white ice crystals against black; the zoom has slightly hazy icy crystals with a faint purple bloom.

The violet halo also acts as a sort of anti-aliasing filter for fine details, significantly reducing micro contrast. This is readily seen on the frosty ice crystals, such as at upper left. The cause is not related to any trivial focus difference; it occurs over a wide range of near to far focus. At center it is not an issue, but quickly becomes apparent over a broad section of the mid zones of the frame. The Milvus 15/2.8 totally avoids the violet haloes along the high contrast edges. The next crop shows this an an even more obvious way.

Below, the same violet haloes are seen on the edges of the pot as well as the wood grain at far left. The Milvus 15/2.8 has a subtly more crisp look to the fine details in the pot; this is due to that violet haloes of the zoom dropping the micro contrast. The total result is an image with more “punch”, more visual impact. Thus the concern is not so much the fine details, but how lifelike the image looks, its brilliance and “pop” to the eye. One need not stare at pixel-level details for the effect to be perceived. I frequently hear comments from my readers to that effect once they have obtained a Zeiss prime.

Flare control

Ghosting flare creates those bright “ghosts” in the image, whereas veiling flare drops contrast. The very best modern zooms handle flare really well, but because they are zooms, they require more lens elements. The ultra wide zooms in the 11-24mm or 14-24mm range utilize bulging front lens elements, which catch stray light (especially the sun), that can result in additional flare issues. With primes, there are fewer lens elements, but a very highly corrected prime also tends to have more elements, so flare generally cannot be suppressed entirely.

As the comparisons that follow show, flare can be a very significant concern. First, an example of the type of scene I might encounter; I count on excellent flare control. Here the sun was just above the edge of the frame. The most dramatic photos can be difficult to make without excellent flare control because even if one wishes to shield the lens, it can be difficult to keep a shielding hand or finger out of the frame.

Canon EOS 5DS R + Zeiss Distagon T* 2.8/21 ZE @ 21mm

[low-res image for bot]

Prime lenses are not immune to lens flare; in color, that dark spot in the middle is a purplish ghosting flare. The crux of the matter is just how much flare occurs. In this shot below the 15/2.8 Distagon has delivered outstanding lens contrast in spite of the intensely bright clouds and the sun in the frame—an absence of veiling flare so that the image retains high brilliance and high contrast everywhere. The one ghosting flare near center is a negative, but flare control is never perfect with any lens. The key point is that the contrast control needed to make this image work would not be viable at all with veiling flare.

Canon EOS 5DS R + Zeiss 15mm f/2.8 Distagon

[low-res image for bot]

Examples of veiling flare and ghosting flare

In this 2-way example, I sought to show each lens at its worst possible flare performance while utilizing a dark background. The Milvus 18/2.8 handles the sun with aplomb, generating a few small ghosting flare spots and no veiling flare. The zoom has flare that ruins the image.

In this 3-way flare comparison, the Milvus 18/2.8 prime controls flare the best (and keeps it to a blue/violet shade). That some zooms are more prone to flare can be seen here: the ultra wide zoom (Zoom 2) has many more flare spots than the more moderate wide angle zoom (Zoom 1).

Focus shift, the bane of sharpness

Now we come to what I consider the most egregious optical behavior, the one that is most likely to disappoint the photographer. On high-res digital, the depth of the zone of focus that is critically sharp (resolved to sensor resolution) can be very limited, even at f/8. Precise focusing for the intended visual impact is thus critical. But what happens if the lens itself changes focus on its own after focusing? That is, it focuses differently at each aperture even as the focus setting remains unchanged. There are additional complications in some cases: focus may shift forward in the outer zones even as central areas shift rearward, which can be confusing and frustrating. Zeiss wide angle primes minimize such behaviors to nil, or nearly so.

Consider the image below. It relies on pinpoint focus to make the leading aspen sharp. But if a lens shifts focus, the same shot at f/4 or f/5.6 would lead to a very sharp distance, and a not-quite-sharp key element (the leading aspen). The Zeiss 21/2.8 maintains focus no matter which aperture is used. As a practical matter, stopping down a lens with focus shift to check focus just does not work in such situations—too dark.

For more on focus shift, see the dozens of articles on focus shift at diglloyd.com. For a wide angle zoom comparison, see this page (requires subscription).

Canon EOS 5DS R + Zeiss Distagon T* 2.8/21 ZE @ 21mm

[low-res image for bot]

Focus shift is not a mechanical issue, but an optical one. It is a behavior whereby the optimal focus varies with each aperture. It is far more common than most photographers realize. There are ways to deal with focus shift; see Focusing ZEISS DSLR Lenses For Peak Performance PART ONE: The Challenges. Since conventional DSLR cameras utilize autofocus with the lens wide open, one cannot easily deal with focus shift when using conventional autofocus.

Focus shift is a potential issue with all lenses, but all recent Zeiss DSLR and mirrorless lens designs control focus shift to nearly nil—not so with some zooms, including wide angle zooms. Even some “slow” f/4 zooms have very strong focus shift, though that particular zoom is not shown here. Nor is focus shift a function of lens price; at least one very expensive zoom suffers from it. The tradeoffs in lens design that lead to focus shift are fewer for a prime lens.

To demonstrate a moderately troublesome case, consider the pairs of images at f/2.8 and f/8 below. One pair was taken with the Milvus 18/2.8 and the other with a zoom (each focused at f/2.8). Similar results were seen with the Milvus 21/2.8 and Milvus 15/2.8 versus the same zoom but these are not shown here. The point of peak focus at f/2.8 is not matched exactly between the two lenses, but that is not relevant for this purpose.

What matters is that the Milvus 18/2.8 holds focus, sharpening up both the foreground and background. The zoom hurls its zone of focus so far rearward that even at f/8, sharpness is visibly degraded at f/8 versus f/2.8. The loss of sharpness is readily seen at bottom left. Amazingly, the increased depth of field at f/8 cannot make up for the severe focus shift with the zoom, so its f/2.8 is sharper than f/8 in the leading areas! Such behaviors make a laughingstock of MTF charts vs real world photography: if the entire zone of sharpness is displaced (usually rearward), then the visual impact intended by the photographer may be irreparably damaged (“blurry eyes, sharp ears”).

With focus shift, it can be a serious challenge to make an optimally sharp image with sharpness where intended; in essence it means focusing error. First the photographer has to know the lens behavior (focus shift can differ with focusing distance also!), and then that behavior has to be compensated. The “fine focus adjust” approach cannot fix such errors, since optimal focus changes with each aperture. Focus shift is particularly problematic with a DSLR shot with conventional autofocus, since the AF mechanism does not account for the shift relative to the shooting aperture.

Focused at f/2.8, shot at f/2.8 and f/8, crops from center

Mechanical and operational benefits of Zeiss primes

Focus stays put

Out in the field there are many situations where I want to pre-focus, knowing that because the lens is manual focus, it will stay put where focused, regardless of whether I turn the camera on/off, press the shutter release slightly, etc.

It has been my experience in the field that autofocus zooms carry the risk of too easily altering focus or zoom: I’m often working in difficult conditions. This might not be a concern in many other circumstances, but it is for me. Most troublesome of all: some zooms exhibit subtle “zoom creep” if the zoom is tilted up or down at an angle, making the lens entirely unusable for some purposes (remember, few if any still-photo zooms are not parfocal). I like my gear to behave with no surprises.

Video

Excellent focus throw as well as a declickable aperture make the Zeiss Milvus lenses an outstanding choice for video applications—a lens that can do double duty for still photography or video is a big plus.

Out in the field using magnified Live View, the focus throw and overall manual focus feel is a pleasure to work with as compared to manual focus with twitchy zoom focusing ring. Inadvertently grabbing the zoom ring instead of the focusing ring is something I do fairly often with a zoom; this operational hassle goes away with a prime lens.

Focus stacking with a prime lens

See Depth of Field Challenges: Bypass the Limits with Focus Stacking, Near or Far, Macro or Landscape.

Focus stacking with a manual focus prime lens in magnified Live View is my preferred way to operate for landscape and similar photography. With a prime, there is no zoom ring to accidentally touch (a significant concern with gloves in cold weather), and I can (in Live View) carefully place focus where needed without any back and forth headache of trying to persuade autofocus to focus on what may be a slanted or indistinct surface. In addition, the focusing throw and feel are far superior. There is also the potential to use the distance scale on the lens to quick a focus bracket quickly, by distance marks.

In a scene like the one below, I’m much happier having high quality manual focus for getting just want I want for focus; many of the spots require some judgement on biasing the focus slightly nearer or farther.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 28mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon

[low-res image for bot]

Conclusions and recommendations

Operational, ergonomic and image quality factors all are worth considering when choosing a zoom lens versus a prime lens. The most obvious decision point of “sharpness” is not actually the major factor as compared to the very best zooms available today, which are quite sharp. Rather, consider the operational and ergonomic factors along with total image quality, particularly in demanding shooting conditions.

To make a personal choice, I recommend shooting real images in a wide variety of lighting and with varied subject matter in order in order to see that all these factors really do add up—in my experience they do, and the rewards of a prime lens are well worth it for many applications. Nothing persuades like the total visual impact delivered by a lens, as seen in one’s own images.

As of 2017, my favorite Zeiss DSLR ultra wide is the 18mm f/2.8 Distagon because of its relatively compact size and weight and a nice spacing between 15mm and 21/25mm. It’s a close call against the Milvus 21/2.8; choose according to how wide you want to go. The Zeiss Milvus 15/2.8 is a very fine choice, but many photographers find it just a bit too wide for general use—that’s why I prefer 18mm most of the time.

Lloyd’s photography blog is found at diglloyd.com; it covers many brands, lenses, cameras. In-depth review coverage of the Zeiss DSLR lenses for Canon and Nikon is found in Guide to Zeiss DSLR Lenses. By subscription.