Zoom Lens or Prime? 135mm

Related: apochromatic, Canon EF 70-200mm f/2.8L, depth of field, distortion, external articles by Lloyd, flowers, focusing, How-To, image stabilization, lens mount, Live View, loupe, Nikon AF-S 70-200mm f/2.8G ED VR, optics, Populus tremuloides, swing and tilt, tripods and support, Zeiss, Zeiss 135mm f/2 APO-Sonnar, Zeiss APO, ZEISS Lenspire, Zeiss Milvus, zone of focus, zoom

by Lloyd Chambers, diglloyd.com

Having discussed ultra-wide angle and moderate wide angle and normal lenses, this is the 4th article of a multi-part series discussing the “zoom versus prime” question. This article goes to the outer end of the Zeiss DSLR lens range, to 135mm.

Prime lens = lens having a fixed focal length and thus fixed angle of view, e.g., 135mm.

Zoom lens* = lens having a continuous range of focal lengths and angle of view, e.g., 70-200mm.

Prime lenses are specialized instruments. In the medium to moderate telephoto range, if the shooting needs are sports or action or several focal lengths or autofocus are needed, then there is no debate: a 70-200mm zoom offers all-in-one flexibility for which a manual focus prime lens is ill-suited. Still, versatility is not always focal length, but other performance aspects such as sharpness corner-to-corner, sharpness through the focusing range (near macro to infinity), distortion, a stop faster lens speed at 135mm, stability mounted on a tripod, minimal breathing for video applications, as well as size and weight for portability.

For this article, I’ve pitted the Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2 against the two finest 70-200mm f/2.8 zooms from Canon and Nikon. The Canon 70-200/2.8L II is a very fine lens, but in my view the Nikon 70-200/2.8 FL ED VR is the finest 70-200mm ever produced and it sets a high bar commensurate with its high price—a suitable challenge for the Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2.

What I am looking for in a lens includes high contrast and micro contrast, consistent performance across the frame, low distortion, flare resistance and in general consistent performance under all types of lighting conditions. But even more important at 135mm are two key shooting concerns: focusing and stability.

Making a sharp image: focusing and stability

This discussion necessarily comes first, because at 135mm there is hardly any margin for errors: the optics are a tertiary concern if perfect technical execution is not achieved. Any sports shooter knows that a small focus miss is a Big Deal, hence years of advances in DSLR autofocus systems. For outdoor photography focusing is an issue also, because the zone of sharpness is critical to a persuasive image, even 100 meters out (at 135mm).

When I started this piece, I did not relish working at 135mm, knowing just how hard it would be to fairly compare the lenses—and my apprehension was not misplaced. That is why I shoot numerous comparisons, and then select ones that are well matched and thus can speak to optical performance.

Two issues in particular are serious challenges when working with telephoto lenses. In practice they can easily outweigh optical performance for field work:

- At 135mm, a “small” focus error is rarely solved by using f/5.6. But even if f/5.6 or f/8 sharpens the desired area optimally (that would be a tiny focus error with a 135mm), the zone of sharpness is displaced in a manner which disrupts the desired visual impact.

- Stability (vibration) is the bane of shooting outdoors with a telephoto lens; even a little wind is a big problem. This is a Big Deal for lenses that mount via a lens tripod foot.

Why speak to these two issues here? Because outdoor photography sums together the lens performance and the ability to to utilize it. The Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2 is a stop faster than an f/2.8 zoom (focusing concerns), and it does not require use of a tripod foot (vibration concerns). Both of these dovetail into the fact that the most pleasing light is generally low light around dawn or dusk, precisely where these two issues come to the fore.

Stability and vibration

The Zeiss Milvus 135/2 allows the camera to mount directly to the tripod head (far more stable). The 70-200mm f/2.8 zooms must be mounted via the lens tripod foot*, and this is a stability disaster**. Modern-day tripod feet are an anti-feature in terms of lens stability. This is not an issue solvable by a heavier tripod. It stems from a mechanically unsound design which in essence puts the lens on a seesaw where the slightest input oscillates through the lens (a puff of breath can be seen to jiggle the image in magnified Live View). It is why dual tripods are wise for super telephotos—to support both lens and camera. And it’s why handheld shooting with image stabilization can be better than a tripod in some situations.

What I always see in the field when working with 70-200mm f/2.8 zooms is the far greater instability in Live View: zoom in to actual pixels in Live View, and the image shakes like jello with a 70-200/2.8 mounted via its tripod foot. Try to focus manually and just touching the lens makes the image jiggle, which makes manual focusing significantly more difficult. A simple A/B focusing exercise between the 70-200/2.8 and the Milvus 135/2 makes the stability difference obvious—the Milvus is far more stable since the camera is mounted, not a seesaw lens foot. Wind and shutter vibration both wreak havoc with the seesaw tripod foot design on a 70-200/2.8.

As shown at right, even the excellent Really Right Stuff LCF replacement tripod foot cannot evade this core issue, because the lens/camera are supported via a small pivot area, which becomes a fulcrum for oscillations.

* Asking the camera lens mount flange to support a 3+ pound lens is asking for trouble. This stress is rarely codified, but as one example: the Leica R-Adapter-M user manual speaks directly to this issue: “up to 700g direct attachment to camera possible”. That is far lower than the weight of a 70-200/2.8 zoom. And it is not just weight, it is the torque exerted by weight away from the camera mount. A slightly off-kilter lens mount causes sharpness problems (20 microns will suffice, 50 microns is a serious problem). Asking the lens mount to support a 70-200/2.8 zoom all by itself is unreasonable, and to let that mass swing around while walking or to bump it even mildly is to add to that stress.

** The best-designed tripod foot designs I’ve seen include the Nikon 50-300mm f/4.5 ED and the Leica 280mm f/4 APO-Telyt-R. The tripod foot on each of those lenses is beefy and adjoins the lens with no gap, minimizing the seesaw oscillations—but it is not a cure.

Focusing

The best light for outdoor photography is usually around dawn or dusk, which often means that when the light is dim, focusing is more difficult (Live View becomes grainy). Particularly with telephoto lenses such as 135mm, focusing is absolutely critical.

An f/2.8 lens makes precise focusing harder than f/2. Not only is it half as bright, it has more depth of field, so the image does not snap into focus as easily. This matters in the shooting situations I most often shoot in (dusk in particular). I know this from years of experience, and every comparison I shot for this article affirms that idea; it was definitely harder to decide on ideal focus at f/2.8 than at f/2.

When I focus manually, it means magnified Live View at actual pixels using a high quality loupe like the Zacuto 3X Z-Finder loupe. Though that might sound like a panacea for perfect focus, over a decade of working a huge variety of cameras and lenses has taught me otherwise. Still, it has proved to be the most reliable and consistent method for getting an optimally sharp image (with mirrorless, magnified Live View using the EVF is the loupe equivalent).

Field Shooting Examples

Examples are all at medium or far distance for a simple reason: anything close introduces perspective as an issue, perspective being determined by the entrance pupil to subject distance. It is complicated to determine and align lens entrance pupils ), let alone swap between camera-mount and tripod-foot mount. Even at distance, vagaries of distortion and rotation (lens collar on the zoom) and internal optical lens group centering always deliver a slightly different framing.

While the Milvus 135mm f/2 goes to near macro range of 1/4 life size, I almost use it for distance work. Its sharpness and very low distortion and minimal 'breathing' make it an excellent choice for single images or stitched images or focus stacking. Thus its far-field performance is highly relevant to how I would shoot it. Moreover the most demanding challenge for a lens is at infinity focus. Focused there, the slightest asymmetry across the field shows up (from either the lens or camera flange/sensor alignment). The image circle is at its smallest, so that vignetting is strongest and corner performance is often challenged. Field curvature is also a factor.

What I look for is total sharpness and how consistent in total a lens is; this is why I like to shoot many comparisons and in so doing arrive at a consensus conclusion— one “quick comparison” or even two or three is problematic. Better to shoot at least five to ten, with subject matter that will ferret out behavior, in order to see that differences are maintained and thus that conclusions are valid. That process naturally eliminates the occasional unfair comparison when one lens is focused not quite optimally.

About the zooms

The Canon zoom was my own personal copy, like new and little used. Good as it ever was.

The Nikon zoom was obtained from LensRentals.com, well known for checking their lenses carefully. As all the examples proved out, the zoom skews its sharpness closer on the left side. Lens skew is very common with lenses and to be fair to Nikon I’ve seen Zeiss Milvus samples with lens skew also. But consider this: a prime has only to focus; a zoom must both focus and zoom—and I don’t think I’ve ever tested a zoom that is symmetric across the field across the zoom range. The odds favor the prime with its lower complexity.

Example #1, Nikon D810: Creek Amid Forest

Where to focus here? The yellow flowers are about 100 feet / 30 meters away. If focus is on the closest yellow flower, then the farthest one is slightly blurred, and vice versa. I chose to focus on the larger boulder just to the left of the yellow flowers, using the boulder in front of it as a check that focus was spot-on. Such nuances are why comparing should not be done with “quick tests”, but a series of evaluations over differing subjects.

The zone of focus (roughly speaking) should cut through the aspen trunk at left, the focused-upon boulder and the large tree and small aspen at right. This is what the Milvus 135 does. It turns out that this scene explains what is seen in other comparisons between the two that I shot: the zoom has a slight skew that places its sharp focus closer on the left side as seen in the pine needles and aspen leaves at left and the blurred background behind. This kind of skew is not unusual, and I am not going to judge the Nikon zoom by it in general, since a sample I shot a few months prior showed excellent uniformity. My comments reflect the best performance of the zoom, not this sample-specific behavior.

I shot the entire aperture series through f/11; my comments reflect that also. Examining the entire frame at full resolution and looking for the best from each lens near to far, the focus seen at f/2.8 is as well matched at center as one could possibly hope for in field conditions, but the Milvus is a hair farther away than the zoom—such nuances cannot be seen even at actual pixels Live View—that’s life in digital.

The Milvus is better at f/2.8 as might be expected as it is one stop down from full aperture, with the zoom being wide open. Going to f/4 the two lenses are performing comparably at their peak area of focus for each, at least in central areas. Going to f/8, the relative performance is comparable if one looks for the best from each in that area. In other words, the zoom is very competitive when stopped down a little (assuming a sample with symmetric performance were obtained). Setting aside the symmetry issues in the particular zoom, the Nikon zoom looks to be state of the art.

View f/4 frames: Milvus image and zoom image.

View f/8 frames: Milvus image and zoom image.

Of course with water some blur can be attractive; see the f/11 image.

This is the high Eastern Sierra in August—not all of it is dry and barren! A wonderful mixed scene here with pines and aspen and willows; it is unusually diverse and caught my eye for that reason.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2

[low-res image for bot]

Crops

The two lenses offer nearly identical performance at center, differing only because of a slight difference in the actual focus point.

View: actual pixels crop.

The correct zone of focus distance cuts through the aspen tree trunk. Towards the left side, a substantial zone of focus discrepancy develops with the zoom. Using f/11 (not shown) is almost but not quite enough to deliver sharpness for the zoom on the aspen trunk.

View: actual pixels crop.

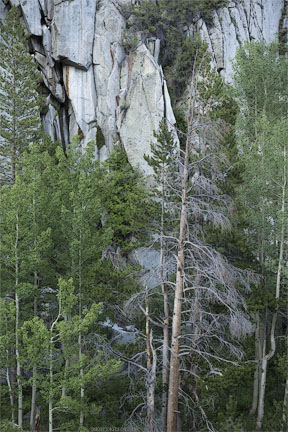

Nikon Example #2: Trees Against Sheer Cliff

This example illustrates just how critical focus is with a 135mm lens: the dead pine tree is quite a distance across a ravine and creek, perhaps 40 meters, maybe more. I focused carefully at f/2 and nailed the focus with the Milvus 135/2; the tree is sharp from top to bottom (f/2.8 is shown here) and there is excellent sharpness across the frame and into the corners in that zone.

The zoom image (not shown) was also sharp at the point of focus on the tree; I manually focused and cross-checked against autofocus as well, focusing at the same point on the tree. I checked the background as well for a similar amount of blur, to the best of my ability in magnified Live View. And yet most of the rest of the frame is quite unsharp for the zoom (which is why I’m not showing its image here). That’s the sort of thing I consistently found in shooting the Milvus against the zooms: I’m able to nail the focus with the Milvus, but have trouble with the zooms. The foregoing is not a claim that the zoom is unsharp optically, only that I find that I can focus better at f/2 with the Milvus. Optimal sharpness requires pinpoint focus hence the lens that makes focusing consistently more accurate is de facto the sharper lens (assuming it is also excellent optically).

Examine the high resolution image and see what a brilliant result the Milvus 135/2 delivers in this mostly-corrected blue canyon light, but also just how blurred the cliff is. Precision focus is a top priority for any shot with this kind of depth, and it paid off here for the Milvus.

View large f/2.8 image.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2

[low-res image for bot]

Nikon Example #3: Aspen and Boulders by Creek

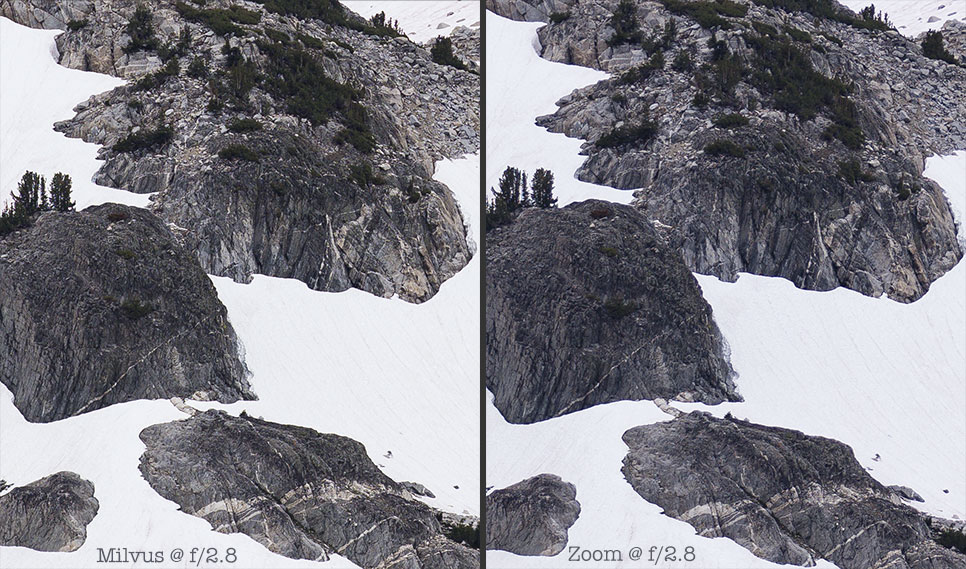

There is an outstanding focus match between the Milvus 135 and the zoom here, as determined by seeing the sharpness of the central aspen and the amount of blur for both lenses on the pine tree to its right.

This is at close range, and at closer range lens performance can differ significantly from performance at distance. Here I am confident in saying that the Milvus offers a sharper image with superior micro contrast, and does so across the frame and where it is supposed to do so. One way to fairly assess this is to look for peak micro contrast on a slanted area, e.g., the dark lichen-covered rock t the right of the central aspen.

View f/2.8 images: Milvus image and zoom image.

Below, peak micro contrast can be assessed using the slanting rock face. The Milvus shows higher sharpness and micro contrast.

View f/2.8 actual pixels crops: Milvus crop and zoom crop.

Nikon Example #4: White Aspen Grove

Reiterating the previous comments: more accurate focus with the Milvus delivering a nice sharp cut across the grove of trees, exactly as I had intended. It’s not that the focus is off by much (a foot or two too forward with the zoom), but that matters and even at f/8 the difference can be seen (comments based on examining the full aperture series from f/2 through f/8).

View f/8 images: Milvus image and zoom image.

Canon Example #1 Saddlebag Lake Dam View to Mt Conness Spur

Images with the 50-megapixel Canon 5Ds R, something to bear in mind for the actual pixels crops.

This example shows a far field shot. Neither lens is perfect.

I shot an aperture series (f/2 or f/2.8 through f/8) for both lenses:

- No filtration used.

- Focus near center of frame, with best focus verified at 16X Live View.

- Field of view does not match exactly; this is very hard to do with differing distortion and mounting (camera base versus tripod foot on lens). The zoom has a slightly higher magnification and thus a slightly unfair advantage.

There is a corner darkening with the zoom even at f/5.6—see top left. Distortion is at most 0.5% pincushion into the extreme corners with the Milvus 135/2. Correcting it shows hardly any visible change except for the corners. This is important: distortion correction for pincushion distortion must stretch pixels apart, which damages micro contrast. The zoom has a modest level of pincushion distortion, but correcting it shows a significant and obvious stretching of the most important part of the frame, the central 3/4 or so. In effect, correcting this distortion lowers performance so what is shown here is its best performance without that correction.

What I first noticed was the accurate color of the Milvus 135/2, which using the appropriate sunlight white balance I determined for the 5Ds R, rendered the rocks with natural color. The zoom imparted an overall magenta cast to all the rocky areas, even though careful checking of white balance and tint on snow and dam-facing matched exactly for the two lenses (a 10 pixel Gaussian blur works well for such checks). That color tint is left intact as shown here, both images processed at 5500°K, with Tint= +8M.

Focus was at the center. Both lenses show weakness on the left side; center and right are better; both appear focused too closely on the left side. The dam at bottom left is “too sharp” with a blurred background, with the zoom just a little better, but both are off. But at top left, the Milvus is better. A perfectly symmetric lens at infinity is relatively rare. I’m looking for best overall performance with a lens and such things have to be taken into account with all lenses— evaluate the entire image for total quality and with a variety of scenes.

View: high-res Milvus frame and high-res zoom frame. Both frames at f/4.

Canon EOS 5DS R + Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2

[low-res image for bot]

Center crop

Any well designed and built lens should perform well in the center, so we should not expect a large difference here. Still, the Milvus outperforms the zoom through f/4 with better micro contrast. At f/5.6 the two lenses are very close, but the veiling magenta cast of the zoom is unappealing.

View f/2.8 at actual pixels or view full series from f/2 through f/8 at actual pixels.

unknown camera, unknown lens

[low-res image for bot]

Top right crop

I’ve chosen f/4 to make the differences most obvious, but while the gap closes with stopping down, the Milvus is already at peak performance at f/4. View the full size crop.

Bottom right crop

At bottom right, both lenses need some improvement, and stopping down will do that. But the zoom is weak along the entire right side, and if that is a skewed lens or field curvature, then it must be far in the distance (“beyond infinity”) because the leading water is not sharp. View the full size crop.

Canon Example #2: Collapsed Tioga Pass Resort

The previous example left me no doubt as to the better performance of the Milvus 135/2, but there were some mixed-performance results over the frame. This example shows how to rule out those doubts: it incorporates a subject that offers detail in front of and behind the chosen point of focus. Doing this helps rule out any bias with slight focus errors, sample-specific asymmetries, etc. When a lens is sharper than another in front of focus, at focus, and behind focus, it is unequivocal evidence that it is outperforming.

View the large entire-frame images: Milvus 135/2 and the zoom. Even at reduced size, the clarity and detail of the Milvus is starkly apparent. See the crops that follow. The roof really is bowed-down; the snow did that.

The Tioga Pass Resort main building was severely damaged in the 2016/2016 from record snowfall, with many of the cabins damaged as well. After a 100+ year run, it seems unlikely it will ever be repaired.

Canon EOS 5DS R + Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2

[low-res image for bot]

Crops

Below, the roof crop shows that the Milvus resolves fine details better than the zoom and is free of the hazy look seen with the zoom. The background with the Milvus is no less sharp than the zoom and yet the foreground (next crop) is hugely sharper. There is some of that same magenta haze with the zoom as seen in the Saddlebag Lake example.

View at actual pixels: roof crop.

unknown camera, unknown lens

[low-res image for bot]

Below, the Milvus 135/2 offers a far deeper zone of sharp focus extending well in front of the building. This is what I term “real depth of field”—it results from very highly corrected optics.

View at actual pixels: foreground crop.

unknown camera, unknown lens

[low-res image for bot]

Canon Example #3: Lee Vining Creek Waterfall

I chose this subject for two reasons: (1) blue canyon light at dusk (hard for a lens), and (2) significant near/far depth suitable for a 135mm lens (for reasons similar to the Tioga Pass Resort example).

Here something unfair is done: the Milvus is shown at f/2, while the zoom is shown at f/2.8. After all, if there is one stop more lens speed and the results are as good or better at that faster stop, this is a win: better and a stop faster is awfully nice.

See the crops, but the Milvus 135/2 delivers a much sharper image from the bottom of the frame to the top, and in all four corners. At reduced size, the benefits are not so obvious, but see the high-res versions.

View: Milvus frame @ f/2 and zoom frame @ f/2.8.

Canon EOS 5DS R + Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2

[low-res image for bot]

Bottom right crop

The Milvus 135/2 does well everywhere by comparison. This crop is representative of the differences seen in the rest of the frame. The zoom delivers soft detail lacking in micro contrast.

View: Milvus frame @ f/2 and zoom frame @ f/2.8.

Canon EOS 5DS R + Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2

[low-res image for bot]

Conclusions and recommendations

The Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2 offers a combination of pinpoint focusing (f/2), greater stability (no tripod foot) and top optical performance. Taken together, the argument is compelling for outdoor landscape-style shooting where lighting conditions and wind are frequently a factor. Thus it is not duplication to also have a 70-200/2.8 zoom and use it when it is the best tool for the job. And to use the Milvus 135/2 for landscape and similar static-subject shooting. And for those like me that frequently hike: the Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2 is not a small lens, but it fits into my daypack far better than a 70-200/2.8 zoom.

Also worth noting: the Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2 focuses to 1:4 (1/4 life size) whereas the zooms cannot go quite as close (1:4.7 is very good for a zoom). However, the zooms shorten their focal length at close range, so that (marked) 135mm is actually a wider field of view—as short as 90mm. If the intent is semi-macro work, the prime is more flexible, and retains its performance and low distortion and excellent color correction at close range and is much easier to manage than having to use a tripod foot.

Lloyd’s photography blog is found at diglloyd.com; it covers many brands, lenses, cameras. In-depth review coverage of the Zeiss DSLR lenses for Canon and Nikon is found in Guide to Zeiss DSLR Lenses. By subscription.