Zoom Lens or Prime? Moderate Wide Angles (25mm, 28mm, 35mm)

Related: apochromatic, astrophotography, depth of field, digital sensor, Eastern Sierra, external articles by Lloyd, field curvature, focusing, How-To, peak bagging, Pine Creek, shutter, Zeiss, Zeiss APO, Zeiss Distagon, ZEISS Lenspire, Zeiss Milvus, Zeiss Otus, zoom

by Lloyd Chambers, diglloyd.com

This is the second article of a multi-part series discussing Zeiss DSLR prime lenses against the best native zooms. The first article discussed 15/18/21mm and spoke to more general behaviors. Here I want to get more specific, showing what the best available moderate wide angle 28mm prime lens offers against a pro-grade zoom.

Prime lens = lens having a fixed focal length and thus fixed angle of view, e.g., 28mm.

Zoom lens* = lens having a continuous range of focal lengths and angle of view, e.g., 24-70mm.

In the moderate wide angle space, the Zeiss lineup for Canon and Nikon includes the classic 25/2 and 28/2 and 35/1.4, the Otus 28/1.4 APO-Distagon, and the Milvus 35/2. I have written about them over the years and I have all of them, but this article focuses on the Zeiss Otus 28mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon because it is a reference-standard by which all others are judged, and it offers a clear-cut win over zoom lenses.

As in part one, the goal of this article is to establish by “tell and show” a conceptual framework by which one evaluates the “prime or zoom” choice for one’s own work. Accordingly, this is not a comparative lens review, but discusses what the best prime can do in general, and in a specific comparison, what it delivers versus a pro-grade zoom. The end goal is to have the reader understand the issues involved in making a decision of prime versus zoom for his/her own particular photographic applications by making an evaluation most appropriate to particular photographic goals.

Why use an f/1.4 prime lens? Why an Otus?

Part one discussed general prime versus zoom considerations, but the Otus 28mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon is worth calling out for its unmatched advantages over f/2.8 pro zooms:

- Outstanding sharpness and contrast maintained over the entire focusing range including edge to edge sharpness even wide open at f/1.4.

- Strict control over color aberrations, including an absence of violet fringing, even wide open.

- Low distortion, consistent over the focusing range.

- Video ready including minimal “breathing” (change in focal length with distance).

- Two additional stops over most pro zooms for subject separation and/or shutter speeds 2X or 4X as fast as an f/2.8 zoom.

- Greater ease of focusing in dim conditions and first-class images possible at night at f/1.4 with much shorter exposure times. See Astrophotography with Zeiss Otus 28/1.4.

- Evenness of illumination over the frame f/2.8, since vignetting is greatly reduced at two stops down.

- Ideal for focus stacking: precise focus control, accurate distance scale, minimal focus breathing.

- Focusing “throw” and feel are first class, good for stills or video.

What doesn’t the Otus 28 do? It’s manual focus only, large and heavy and 28mm only. Some applications may require autofocus, compactness and a range of focal lengths for fast response without switching lenses.

Isolating the subject

One key advantage of a fast prime lens is subject isolation, as with this image from Zeiss Otus 28mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon: the Reference Standard With a Gentle Grace. With an f/2.8 zoom, this flexibility is much reduced because the depth of field is doubled at f/2.8 versus f/1.4.

At f/1.4 the subject can be set apart from its surroundings even at substantial distance as here. The blur of closer areas and the subtle blur of very distant areas leads the eye to the tree at center, and separates it from its surroundings. The combination of shallow depth of field, superb color correction, high sharpness and moderate vignetting come together nicely in a synergistic total effect. Choices for visual impact and expressiveness are thus more expansive for an f/1.4 lens than an f/2.8 lens. This flexibility is not limited to landscapes; one might for example focus on a particular face within a group.

Sony A7R II + Zeiss Otus 28mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon @ 35mm

[low-res image for bot]

Sharpness and field curvature, prelude to example

Sharpness for any planar subject and particularly at distance is remarkably challenging. Even high-end lenses have difficulty delivering a fully sharp image across the field for the first few stops on high-res digital cameras. Even if focus is perfect (say, at center), any field curvature causes a loss of sharpness elsewhere in the frame. There are more than a few lenses for which f/8 is just barely enough for sharpness across the frame, due to field curvature and/or focus shift and/or astigmatism, particularly in outer zones of the frame.

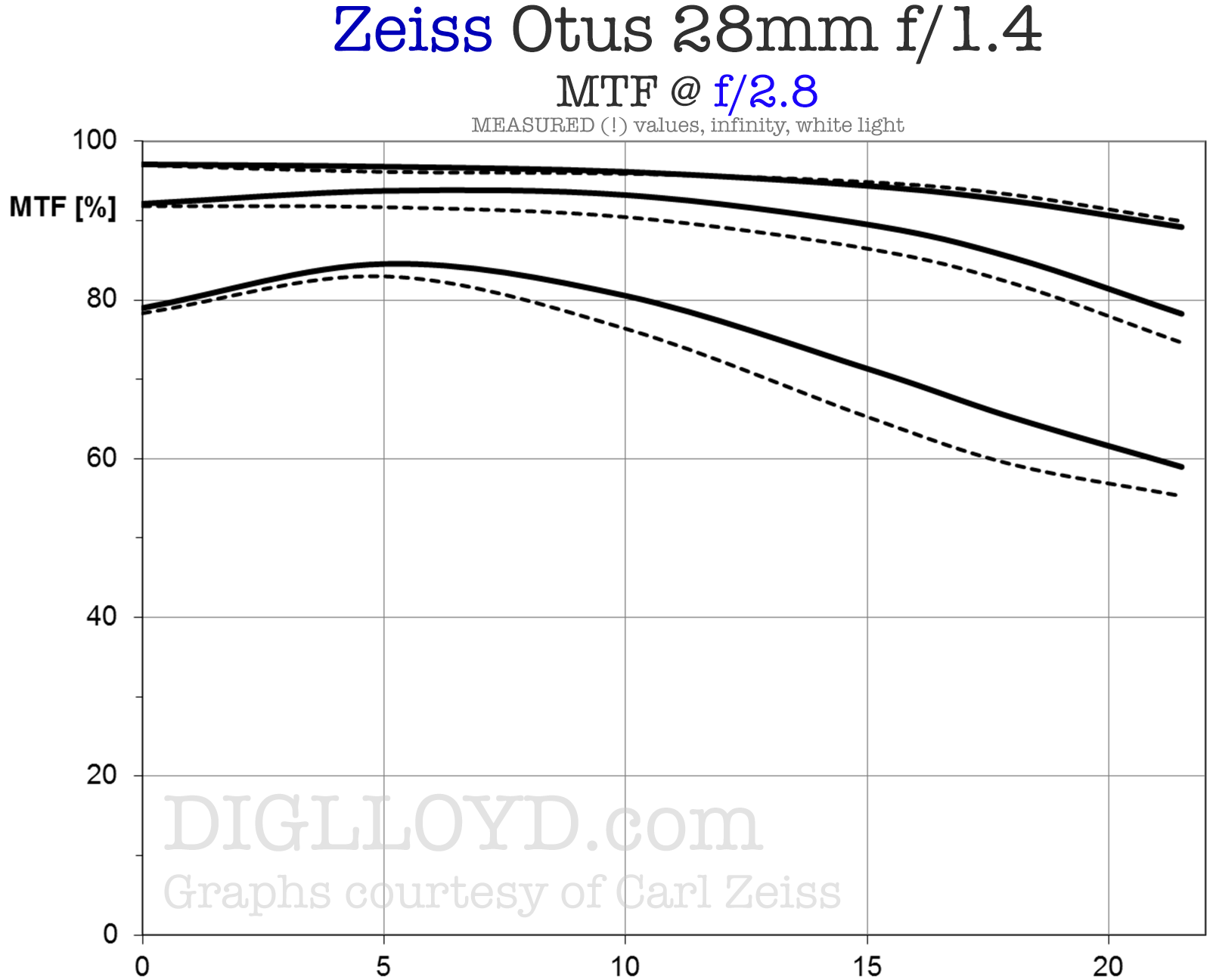

Shown below, the Zeiss Otus 28/1.4 APO-Distagon maintains exceptional sharpness from center to corners even at f/2.8. Bottom pair of lines is 40 line pairs/mm. A value of 80% is world class, with 60% considered excellent, and the Otus does that into the extreme corners.

A zoom lens is compromised for performance across its zoom range. One typical compromise is field curvature, which is allowed to increase substantially. A prime lens has compromises too, but with a fixed focal length it has less to compromise. There are limits to what is acceptable to compromise. For example, I deem a lens that requires f/8 or f/11 for full sharpness across the frame much less useful, because it has more limited applications than a lens with a flat field (minimal field curvature). A lens that maintains a flat field at full aperture is far more useful for distance shooting (the ultimate planar subject), but this is also true of a totally different application such as a group portrait or the front of a building. In handheld shooting, apertures in the range of f/2 to f/5.6 might be mandatory for a minimum shutter speed. A lens that isn’t sharp across the frame for a planar subject has reduced applications.

A planar subject as used here refers to subject matter at a uniform distance, such as a distant landscape, a group of people arranged at relatively uniform distance, a building shot straight-on, stars, etc.

A“flat field” or strictly controlled field curvature is desirable because it becomes possible to shoot even wide open and yet have high sharpness across the frame. Examples where a flat field lens is desirable include not just the obvious landscape distance shot, but also architecture, group portraits and astrophotography. Optimized to include strictly controlled field curvature, the Zeiss Otus 28/1.4 prime lens is sharp wide open across the frame, a feat that few if any zooms or primes can match: the post office box numbers in the image below strain the limits of sensor resolution but can be read in the full-res image at 36 megapixels. A pro-grade zoom would already be at f/2.8 and be very unlikely to succeed.

Below, the Otus 28/1.4 resolves even the numbers on the post office boxes right out to the limits of sensor resolution, wide open at f/1.4. Focus accuracy and a flat field are critical for a planar subject like this.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 28mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon

[low-res image for bot]

The Otus 28/1.4 is ideal for astrophotography because of its strict control of field curvature wide open at f/1.4. At two stops slower, an f/2.8 zoom offers 1/4 the light gathering power and typically has difficulty rendering pinpoints due to field curvature. Dim stars may be difficult to record even at f/2 (let alone f/2.8), and going 4X as long means there is no room for shorter exposures for pinprick stars (instead of star trails). Shooting at f/1.4 with a flat field is thus immensely useful versus an f/2.8 zoom.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 28mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon

[low-res image for bot]

Comparing fairly

What I prize in a lens is its ability to provide total sharpness near to far and across the entire frame. Studying only one location in the frame won’t do, since both field curvature and focus shift vary with each lens design. Also, a perfect focus match is extremely difficult in the field, and if there is any field curvature or focus shift (which there nearly always is), then there exists no way to match focus across the frame. Thus the persuasive and defensible argument is showing that one lens is better than the other at close range and medium range and far range, thereby preventing erroneous conclusions stemming from focus placement or focus shift or field curvature or any particular portion of the frame. That is why I shot six different comparisons across several weeks, confirming the results shown here as compellingly in favor of the Otus every time.

The Otus 28/1.4 will not necessarily be superior everywhere in the frame: pro-grade zooms are really good these days and can deliver outstanding results. But our discussion here is about total performance: near to far and over the entire frame, particularly on planar or semi-planar subjects. The Otus 28/1.4 maintains a consistently high performance across the frame at any distance, minimizing variation in sharpness, minimizing field curvature, etc. It can be a trusted tool, relatively free of “surprises”.

Shootout: 9050 Pine Creek Road

Now we get to it: how does the Otus 28/1.4 perform against a pro-grade f/2.8 zoom on a distance scene?

This comparison was selected from among six A/B shootouts taken over several weeks. I chose it mainly because while it is a distance scene, there is still a large near-to-far layout of subject matter, which if anything affords the chance for the zoom to look better than a pure far-distance scene—I wanted to show something realistically “3D” having several distinct “layers” at different distances.

Another reason I chose this scene was for its extreme contrast, looking to challenge the lenses on the flare and contrast fronts as well. The raw conversion pushes Adobe Camera Raw to the limits of its controls. Both lenses do fine on that front (front element shaded for both as is my wont).

For the other A/B shootouts, each of those showed that in every case when the Otus 28/1.4 was shot at the same aperture it easily outperformed a pro-grade zoom. Even so, the Otus 28/1.4 has its own limitations at 50 megapixels (Canon 5Ds R)—extreme resolution reveals all optical shortcomings and/or execution errors, such as anything less than perfect focus.

Below, focus was matched at f/2.8 on the “9050 Pine Creek Road” lettering as well as could be done at full magnification in Live View. Even so, the match is not exactly right: the zoom is sharper near the waterfall area at f/2.8 but degrades rapidly in outer zones. The Otus is slightly out of focus on the rock at the top of the waterfall, as it ought to be, and much sharper in the outer zones, where it ought to be. That this is so is confirmed with the f/1.4 frame (not shown). And that is part of the point: the zoom is not sharp where it ought to be given the choice of focus: its forward-arcing field curvature rapidly comes into play away from the central areas—a very big negative for this scene. The crops that follow show a striking variation.

Magnification for the Otus and the zoom is closely matched to within about 0.5% and shutter speed is identical for both lenses. The tripod was fixed in place. No lens corrections used during raw conversion. Even at f/8, the differences are substantial, though this won’t be obvious at web size—see the crops that follow.

Canon EOS 5DS R + Zeiss Otus 28mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon

[low-res image for bot]

Crops

Extremely large crops would have been far too large for most displays and made it difficult to comment on specific areas. The crops are nonetheless very large; open at full size to best see the differences. All crops at f/8 unless noted. Otus crop at top, zoom crop at bottom.

While the crops are chosen mostly from the right side, the left side shows similar behavior, it’s just that the right side offers better detail to study, and better illumination.

Focus

The two lenses are similar in the left half of this crop, with the zoom actually a little sharper on the rock at the top of the waterfall, showing that the zoom can be very sharp indeed, but this is a zone of focus issue (both lenses nicely crisp on the lettering at f2/.8, which is the point of desired focus). At right the Otus is much more crisp on the distant snow field and building and increasingly sharper at the right side of the frame.

Top right

Definition with the Otus is far superior. See the sheen on the rocks at bottom left, the tree detail at top left, the branches of the tree at right.

Right side

The Otus 28/1.4 shows crisp detail near to far and left to right whereas the zoom is quite blurry at f/2.8 (not shown), but even at f/8 the zoom has no sharp detail for about the rightmost 3/4 of the crop, at any distance.

Bottom right

These crops at f/2.8 because the water at f/8 at 1/640 second goes blurred from motion.

The Otus offers outstanding sparkle and clarity. Even at f/8 (not shown) the zoom does not deliver a crisp image, with the brush at right remaining dull and ill-defined, just as in most of the Top Right crop. Indeed, the Otus at f/2 is easily a match for the zoom at f/8.

However, observe that at top left the zoom is very sharp. The problem is that while it might be sharp over on the right side, that sharpness is probably hanging in mid-air well in front of the brush, due to field curvature. By comparison, the Otus has delivered sharpness consistently across the field. Such field curvature is a key consideration when shooting any kind of planar or semi-planar subject (as here). That is not a statement that this zoom cannot be sharp in outer areas, but it is a statement that it and most zooms often cannot make a sharp image across the field for subject matter at a similar distance (planar). That’s one reason so many photographers shoot at f/11 (or even the unwise f/16).

Mid zone, left of center

Both lenses deliver good sharpness in the leading areas. The zoom struggles to delivers definition at distance, with the Otus delivering very fine detail in brush on the distant slope. The zoom also shows quite a lot more color fringing (red and cyan fringes on high contrast edges such as the branches against the snow). As discussed in the Bottom Right crop, the zoom might in fact be quite sharp in the outer zones, but in mid-air much closer to the camera, which is hopeless for a scene at distance like this.

Summarizing the Shootout crops

The Otus 28/1.4 has delivered sharpness across the frame and has done so at all distances near to far. The total sharpness far exceeds the zoom. Most important, the sharpness cuts through the scene exactly as one would expect—no surprises or guessing, it just delivers a nice clean cut across the frame at the distance it is focused, and builds on that win with the increased depth of field that accrues with stopping down.

The zoom is very sharp in the center but in the outer zones it breaks down badly. This is due to field curvature (and possibly some focus shift in outer zones). Its optimal sharpness for much of the frame presumably hangs somewhere in mid-air—not at all useful for any planar or semi-planar image. One could bias focus considerably more rearwards in order to “balance” its sharpness across the scene better, but that is of no help in a distance scene in which most everything is at the same distance. Even if one an compensate that way, it takes forethought and is of little use for a group portrait or for astrophotography or for the side of a building, etc. A lens with significant field curvature is just the wrong tool for those jobs.

Conclusions and recommendations

A prime lens with tightly leashed behaviors like the Zeiss Otus 28/1.4 has fewer compromises than a zoom, and thus tends to deliver more consistent performance that in effect means sharper results more of the time. The importance for any particular shot can matter a little or a lot, but consistent sharpness near to far and across the frame makes it a tool I can count on with no special thinking-through of oddball behaviors.

Any particular prime or zoom has its own behaviors. As seen here, the zoom could not deliver a fully sharp image across the frame, which is a major drawback for any scene with subject matter at a relatively uniform distance (“planar”). The choice of “best lens” really means “best lens for ____”, so the way to decide is to look at what a lens actually delivers as compared to another. That is what I did six times on different scenes over a period of weeks—I wanted no doubt to remain as to which lens could deliver the best results. In the end, examining all the A/B comparisons, every one of them stood out in favor of the Otus 28/1.4. Thus the zoom should be relegated to what zooms do best—shooting when zooming and autofocus are required.

Lloyd’s photography blog is found at diglloyd.com; it covers many brands, lenses, cameras. In-depth review coverage of the Zeiss DSLR lenses for Canon and Nikon is found in Guide to Zeiss DSLR Lenses. By subscription.