Micro Contrast and the Zeiss 'Pop'

Related: apochromatic, depth of field, diffraction, digital sensor, Eastern Sierra, exposure, external articles by Lloyd, focus stacking, focusing, How-To, lens flare, Lundy Canyon area, micro contrast, MTF, optics, peak bagging, veiling flare, vignetting, visual impact, Zeiss, ZEISS Lenspire, Zeiss Milvus, Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2, Zeiss Otus, Zeiss Planar

by Lloyd Chambers, diglloyd.com

Over about a decade of shooting Zeiss lenses and all the major brands and 3rd party lenses, I’ve developed a sense of what I like in the final image—and that involves contrast, particularly high micro contrast.

As the late Dr. Hubert Nasse said to me some years ago when I was pestering him about lens performance, he replied (perhaps in exasperation at my persistence): “it is the sum of everything”. At first blush, this seems to be a banal truism, but it actually it is a terrific way to sum up lens performance as extremely complex, and not very obvious as to all contributing factors. It neatly sums up why lab tests and MTF charts are a useful starting point, but not a substitute for evaluating real images taken in the field, because in the field the recording of images introduces factors that one might not observe in the lab, such as color of light and subject matter, flare of various kinds, diffraction effects, sensor/lens interaction, etc.

What is micro contrast?

This article focuses on contrast, particularly micro contrast. Preserving the contrast of the subject matter is what makes an image look alive and real. High overall contrast with high micro contrast such as with Zeiss Otus lenses delivers what one might term “pop” or “3D rendering” or “brilliance” or the “bite” of fine details. High overall contrast and high micro contrast deliver a visual impact that is compelling—what we respond to when viewing an image. In low contrast conditions such as overcast skies, shadows at dusk, etc, it becomes even more important for a lens to deliver the maximum contrast, or the image looks even more dull and lifeless. Yet if the lens maintains the scene contrast, then a photograph can be made that is persuasive in its sense of realism of fog or twilight or similar subjects. In the shadows of dusk and similar situations, I term this the “penetrating power” of a lens. More on that later.

One less obvious benefit of high micro contrast is that less aggressive sharpening is needed. When an image has low micro contrast, appropriate sharpening can help—but that can be an issue if noise is significant, and sharpening tends to reduce tonal subtlety—an image made “crunchy” grabs the eye but soon wearies it, not looking natural.

Yet another less obvious benefit: a lens with high micro contrast makes manual focus easier, since an in-focus image “snaps” into focus (use magnified Live View for manual focus, the optical viewfinder is not adequate). It also makes the job of the autofocus system easier. Better focusing leads to more “keepers”. Even tiny errors will show up as reduced micro contrast. Finally, a lens having low micro contrast wide open often means spherical aberration, which leads to focus shift which further complicates optimal focusing; see Focusing Zeiss DSLR Lenses For Peak Performance, PART ONE: The Challenges, Challenge #5.

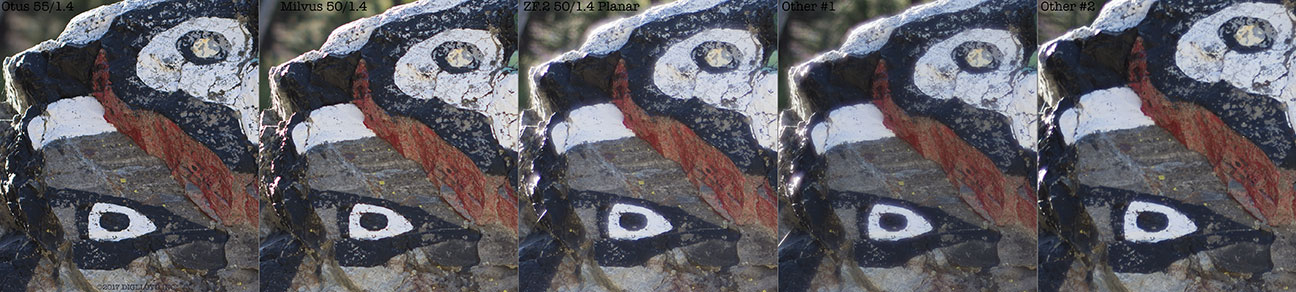

Below: even at greatly reduced size, this 5-way comparison of 50/55/58mm lenses shows the striking differences in both overall contrast and micro contrast. See the 5-way crop and the 5-way image stack. See how the Otus 55/1.4 image “pops” and look far more lifelike. And it doesn’t just have better contrast, there is more actual detail over a deeper zone—more “real depth of field”. The Milvus 50/1.4 is next best, but does not have the same “bite” that the Otus offers (though stopping down closes the gap fairly quickly).

Below is the Otus 55mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon image. See the 5-way full-frame images at half camera resolution. The Otus image exhibits the lifelike “pop” or “3D rendering” that make the best Zeiss designs so attractive. One might hardly realize that this was taken at f/1.4! Its real (actual) depth of field in terms of crisply defined detail is substantially deeper than the other lenses.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 55mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon

[low-res image for bot]

Subject contrast and optical systems

Contrast is the difference between tone, usually discussed in terms of black and white (differences in brightness ignoring color), as distinguished from “color contrast” which refers more to how human vision perceives color. For example, orange set against blue is perceived as particularly striking, even though the actual luminance (brightness) might be low contrast.

In any real photograph containing detail, there is a contrast to the subject matter unless it is something like pure blue sky. But even a blue sky has some contrast from zenith to horizon, being brighter at the horizon and deeper blue overhead. Heavy fog has extremely low contrast; even a very black object near a very white object will look grayish because of the intervening fog. Ditto for atmospheric haze, smoke, etc.

An optical system always reduces contrast from the original scene with less than the original contrast: black becomes slightly gray and white becomes slightly gray, never quite the original (sharpening can actually make contrast higher than the original at the cost of some loss of tonal subtlety, but that is another story).

When a lens is stopped down, diffraction can make a very large reduction in contrast at all levels starting around f/11. For higher resolution cameras (high density photosites), micro contrast per pixel is affected even at f/8 or f/5.6 (high-density APS-C sensors). As the fine-ness of details increases, this “graying” increases: the contrast steadily decreases as the resolution increases, until there is no detail at all (no differentiation in tone, no detail). A camera with a very high resolution sensor cannot perform at its best unless the lens delivers high micro contrast to its sensor. This seems obvious, but plenty of photographers buy 36 or 42 or 50 megapixel cameras while utilizing lenses incapable of resolving to the sensor, or stop down to f/16 or even f/22, thus hammering micro contrast and overall contrast as well. The tradeoff for marginal depth of field gains is usually a losing proposition.

A lens cannot have high micro contrast without high contrast for coarse and medium structures also. For example, fine details on a backlit deeply shadowed hillside cannot have high micro contrast should the lens develop flare: dark details cannot be any darker than the minimum gray established by the flare. The presence of any filter and particularly a polarizer can induce such contrast reductions; always shield the lens from non-image-forming light when possible.

Contrast and aperture, diffraction dulling

Very highly corrected lenses like the Zeiss Otus line quickly reach peak performance. This allows shooting at wider apertures such as f/1.4 or f/2 or f/2.8 with incredible “pop” or “snap”. When set against a blurred background, the perceived sharpness is even higher because in-focus areas have wonderful micro contrast juxtaposed against blur—the image appears to pop out of the background like a 3D cutout.

As stopping down continues the depth of field increases, and in general this can be a fine thing, since small focus errors result in impaired micro contrast on the intended subject. To about f/6.3, peak brilliance is available on cameras up to 50 megapixels (full frame), but at about f/8 contrast at all levels begins to drop from diffraction; see Depth of Field Challenges: Bypass the Limits with Focus Stacking, Near or Far, Macro or Landscape. By f/11 there are substantial repurcussions to contrast and particularly micro contrast which can be mitigated by appropriate sharpening, but the full “pop” isn’t quite there (though the Otus 55 defers the downside unusually well, see the moonlight van example). Using f/16 or f/22 is a recipe for mushy results.

Below, this aperture series using the Milvus 135/2 APO-Sonnar shows what happens from f/2 through f/22 due to diffraction. Be sure to view the full size image.

- At f/2, micro contrast is already very high, becoming almost optimal at f/2.8, albeit with limited depth of field.

- At f/8, subtle micro contrast losses verus f/5.6 become visible (36 megapixel Nikon D810).

- Micro contrast at f/8 is similar to f/2, from diffraction effects.

- Loss of micro contrast accelerates to obvious loss at f/11.

- f/16 micro contrast losses are unaceptable (to me) as a rule, with f/22 never a rational option.

Maintaining contrast when depth of field is needed, avoiding diffraction dulling

How then to work around diffraction, yet enjoy the brilliance of an image taken at an aperture that is more optimal for micro contrast? The answer is focus stacking. The bad news is that some micro contrast is lost in the stacking process. It is also extra work (more post processing). The good news is that there can be huge gains in depth of field, and that micro contrast can be mitigated by sharpening. Morever, overall contrast (coarse and medium structures) is unaffected. The result is an image that preserves the “pop” and brilliance of the originals, but with far superior depth of field.

Below, this 3-frame focus stack with the Otus 55/1.4 APO-Distagon could not come close to this amount of depth of field even at f/16, and yet the high lens contrast makes it through the stacking process unscathed: quality in = quality out.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 55mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon

[low-res image for bot]

Example: contrast degraded by diffraction and flare.

Below, the high lens contrast of the Otus 85/1.4 contrasts with the effects of greatly reduced contrast from both diffraction at f/16 and lens flare. Avoid both: shield the lens from non-image-forming light whenever feasible—even Otus lenses do not control flare perfectly.

The use of f/16 is almost never justified (f/11 or f/13 are OK, but diffraction mitigating sharpening is essential). Micro contrast in the f/16 image in effect destroys the finest details, that is, the contrast becomes too low for detail to be perceived or even recorded. The f/8 image could be processed to brighten the dark areas, with ample fine detail present.

Examples

The Zeiss micro contrast “pop” is evident at every aperture until diffraction flattens performance with a heavy hand as discussed previously and as shown in MTF charts. A key difference with the Otus lenses and lenses like the Milvus 135/2 APO-Sonnar is the high performance wide open, and particularly only one stop down, but also measures taken to minimize contrast loss under varied lighting conditions, with special attention to flare and aberration corrections. The subject color and illumination affect micro contrast, with violet/blue illumination having substantially lower performance with some lenses, but Zeiss APO lenses correct violet/blue extremely well and thus deliver excellent results under any lighting conditions.

It is critical that contrast be held with stopping down at least through f/11, and in that regard there can be surprises even at ideal apertures like f/5.6: contrast losses from internal reflections between lens elements and the sensor. With some lenses that contrast drop can be a significant contributing factor, getting worse with more stopping down. That issue is not diffraction, but this contrast loss which “piles on” to the diffraction losses. Thus it’s worth looking at stopped-down apertures as well, and in a variety of conditions—lens performance in sunlight vs very blue mountain canyon light can differ significantly.

Example: Otus 55/1.4 APO-Distagon: Last Kiss of Light at Bristlecone Graveyard and Nursery

The illumination changed so quickly here that only the f/1.4 exposure satisfied as to its balance and where the light fell—too late for f/2. No matter—while the depth of field is very thin, the Otus 55/1.4 delivers outstanding contrast at all levels. The tree pops out of background, an effect caused by the juxtaposition of sharpness in a thin zone against an out-of-focus background (shallow depth of field). Even if not optimally sharp at f/1.4 (versus f/2.8), it is the overall contrast plus micro contrast that makes the subject stand out against its blurred background.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 55mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon

[low-res image for bot]

Example: Otus 85/1.4 APO-Planar: Healthy Bristlecone

Perhaps approaching 5000 years old, this ancient bristlecone pine survives with thin strips of bark feeding its needles at about 11,500 ft / 3500 meters elevation. The wood weathers like the rocks, decaying extremely slowly.

The micro contrast bite is there right at f/1.4, but in this case, this large tree has a lot of depth and I wanted good sharpness on most of its trunk and its needles, so I went to f/5.6, which maintains all the micro contrast and still provides good separation from the background.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 85mm f/1.4 APO-Planar

[low-res image for bot]

Example: Otus 28mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon: Lundy Reservoir at Dawn

The Zeiss Otus 28mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon doesn’t have quite the same micro contrast wide open at f/1.4 as do its 55mm and 85mm siblings (optical design is much more challenging at 28mm), but it is no slouch by any means and its performance delivers a similar visual impact with a “snap” at f/1.4 that extends over the entire frame, not just aiming for center performance at f/1.4. Quality quickly rises with stopping down.

Getting high micro contrast in this ultra-blue pre-sunrise mountain canyon light requires first-class color correction. It is what helps keep micro contrast high even in violet/blue light like this. See the large actual pixels crop. Here f/2 is shown to reduce the vignetting a bit; f/1.4 is nearly as good. This is *very* difficult lighting for any lens: very blue and very low contast on the dam.

NIKON D810 + Nikon AF-S 28mm f/1.4E ED

[low-res image for bot]

Example: Otus 85/1.4 APO-Planar: Aspen Trunk Wet from Rain

Otus 85/1.4 micro contrast is high when shot wide open, but stopping down to f/2.8 achieves peak performance. Here with Aspen Trunk Wet from Rain, there are several concerns in shooting an image like this at f/1.4:

- Focus acuracy is paramount. Missing focus by a hair is surprisingly easy (and I did so in this case!).

- The tree trunk is not straight; it undulates, so that some portions can be sharp and other not sharp at f/1.4.

- For maximum “pop”, peak micro contrast and enough depth of field causes the image appear to pop out of the background, the “3D” effect. Sometimes this works great at f/1.4 and sometimes the subject needs some depth of field because it is uneven in depth (distance).

Below: when viewed at reduced size, the differences are fairly subtle between f/1.4 and f/2.8*, particularly in the outer zones of f/1.4, where the effective aperture is at least f/2. The f/2.8 image at right gains enough depth of field to sharpen most of the leading edge of the tree trunk and even start wrapping around the sides, yet the background is still pleasingly blurred and the micro contrast is near its optimum on the tree trunk. Setting extreme sharpness against a blurred background makes the sharp areas seem even sharper (even if not fully sharp).

* The f/1.4 image has been corrected for vignetting to make the comparison easier, but I personally often prefer the vignetting at f/1.4, and I leave it uncorrected for nearly all of my images.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 85mm f/1.4 APO-Planar

[low-res image for bot]

Actual pixels crop shown below. I appear to have slightly front-focused so that performance is not optimal at f/1.4 on the trunk. But f/2.8 not only takes care of that, but delivers a solid gain in depth of field. Which makes the point that shooting at f/1.4 is very hard—miss but a little and the visual impact is lost—blurry eyes don’t cut if for portrait. See the full-size crops; the focus was at the top area of the crop.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 85mm f/1.4 APO-Planar

[low-res image for bot]

Example: Otus 55/1.4 APO-Distagon: Sprinter Van by Moonlight

Taken on the maiden voyage of my Mercedes Sprinter photography adventure van, before any upfitting—just a metal box turbo diesel workhorse with my stuff in it.

Here there are two challenging things for a lens: (1) keeping dark blacks black, and (2) maintaining high contrast at edges of dark and bright. The van seems to pop out of the darkness against a rich background (even after being processed to lighten the shadows!). Even at f/11 the Otus 55/1.4 maintains unusually high contrast, which makes f/11 more palatable than it otherwise would be. Here I wanted reasonably sharp star trails, so f/11 was necessary, although the full moon made only the brightest stars visible. Interior color was matched to moonlight using the Cineo Matchbox.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 55mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon

[low-res image for bot]

Example: Otus 85/1.4 APO-Planar: Tenacious Juniper Tree

On a 36/42/50 megapixel camera, micro contrast reaches its peak at about f/6.3 before diffraction starts kicking in significantly, though f/8 can be fine with a touch of extra sharpening to mitigate the small loss. The better the lens, the more the loss can be noticed, since the lens is closer to being limited by diffraction. High micro contrast is important in order to distinguish dark tones from subtly lighter or darker tones, as we have here in the rain-soaked wood, the last light of the day peeping through storm clouds for a wonderfully warm light.

Below, I wanted most of the juniper tree to be sharp, and that required stopping down; at f/1.4 the center of the tree was wonderfully sharp, but depth of field was troublesome. I also did not want too-sharp a background that would merge with the tree. Aperture f/6.3 was just right. See the large actual pixels crop.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 85mm f/1.4 APO-Planar

[low-res image for bot]

Example: Otus 85/1.4 APO-Planar: Backlit Bristlecone (f/1.4 and f/4)

The key thing to notice here is that there is no difference in the 3D “pop” of the image at f/1.4 versus f/4. That makes the lens exceptionally versatile , with aperture not the determining factor for image quality.

Here the 3D pop that results from high contrast is outstanding wide open at f/1.4. But it drops off in some areas of the tree (I focused on the round burl near front, which was too close for the main trunk). The tradeoff is how much background blur is desired: stop down to f/4 (next image), and the sharpness encompasses much of the tree, but also sharpens the background. But at least the choice is not forced by performance limitations at f/1.4, as with most lenses.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 85mm f/1.4 APO-Planar

[low-res image for bot]

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 85mm f/1.4 APO-Planar

[low-res image for bot]

Example: Otus 55/1.4 APO-Distagon: Ghostly Bristlecones at Dusk (f/1.4 and f/4)

As with the 85/1.4 APO-Planar, the key thing to notice here is that there is no difference in the 3D “pop” of the image at f/1.4 versus f/4, though there is enough depth of field at f/4 to make most of the leading tree sharp while still separating it from its background.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 55mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon

[low-res image for bot]

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 55mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon

[low-res image for bot]

Penetrating power: distinguishing dark tones

When shooting at dusk and in murky conditions, a lens must preserve dark tone contrast extremely well or the shadows will go mushy and grayish, merging black with near black, and thus losing detail. High contrast is thus critical to a lifelike image, in order to preserve the nuances of darker tones. I call this ability to “see into the shadows under the trees” (literally and evocatively) to be penetrating power.

Example: Otus 85mm f/1.4 APO-Planar: Snowfield with Algae, Deep Dusk

Red/purple algae (apparently Chlamydomonas nivalis) grows on this snowfield on this shaded mountainside. Shot at dusk in very low contrast and very blue light at f/1.4, the lens must faithfully pass through what little contrast is present in the situation. The Otus 85 has delivered an outstanding image under difficult conditions. White-balanced properly and with appropriate processing, the semi-tesselatted surface of the snow field is clearly delineated—see the large image.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 85mm f/1.4 APO-Planar

[low-res image for bot]

Example: Milvus 135mm f/2 APO-Sonnar: Ancient Bristlecone Trunk and Rising Moon

I wanted to add some balance and sense of place, so I shot this 2-frame focus stacked image to include the bristlecone pine trunk along with the moonrise. The stack isn’t perfect (very hard to do this near-to-far focus at 135mm with only 2 frames), but the Milvus 135/2 APO-Sonnar has peered through the deep dusk to delineate very fine details in the distance and in the wood of the trunk—no easy feat to maintain high micro contrast for monochromatic light or subject matter.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2

[low-res image for bot]

Example: Milvus 135mm f/2 APO-Sonnar: Breached Beaver Dam

Deep in a mountain canyon, late dusk brings low contrast blue lighting. Below, the Milvus 135mm f/2 APO-Sonnar delivers outstanding overall contrast and micro contrast, which together make for a strong visual impact (image processed for moderate contrast in order to allow seeing into/under the trees).

The use of f/5.6 on the 36-megapixel Nikon D810 maintains high micro contrast without fear of dulling losses from diffraction. High overall contrast keeps black and not quite black distinct. Very blue light of dusk (only partially corrected here) presents a challenge that demands excellent optical color correction. Otherwise, fine details can be overlaid with violet/blue haloes; even mild amounts drop contrast.

See the large actual pixels crop which shows fine detail not blurred by the wind and also the crop of the forest area (foliage blurred by wind).

Below, this beaver dam inundated a very large area of the canyon for many years (I saw it 25 years ago though 2016!). It was breached in the spring of 2017 due to extreme runoff from record snowfall. The beaver has set up shop in a lower meadow area. I do not think it will return and fix the dam, due to too many visitors.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2

[low-res image for bot]

Example: Milvus 135mm f/2 APO-Sonnar: White Mountains Sunrise

I knew the sun would have to blow out, but that maintaining the area around the sun required a very dark (nearly black) exposure level for the foreground hills. The exceptional lens contrast even shooting into the sun kept those deeply shadowed areas black, without a graying veiling flare. I was able to substantially boost the shadow areas in brightness while retaining good detail and tonal separation.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2

[low-res image for bot]

Example: Zeiss 55/1.4m APO-Distagon: Bristlecone View to Brilliant White Cloud at Dusk

The foreground was very dark, and the cloud very bright, offering up the possibility of a veiling flare, but the Otus 55/1.4 kept the dark areas dark. This is a very difficult exposure and was tricky and bit frustrating to process. I shot it to show that the nearly-black foreground can be brought up with good detail, because that very bright white cloud does not add any veiling flare to other areas of the frame.

I shot one frame at f/8, focusing on the downed tree root area, knowing that depth of field would leave a blurry foreground and background, even at f/8. Then I shot two more frames for a focus stack. This is the 3-frame focus stack.

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Otus 55mm f/1.4 APO-Distagon

[low-res image for bot]

Example: Milvus 135mm f/2 APO-Sonnar: Dying Aspen

Below, it had just stopped raining, and I shot into these deeply-shadowed trees. There was a faint haze in the air from water vapor, so I pulled down the blacks a small amount. Because the 135/2 APO-Sonnar has cleanly separated all the dark tones, the dark areas show detail and clear separation. Here at f/4, depth of field is just adequate for high sharpness on many of the trees. See the actual pixels crop (sharpest near, fades off behind).

NIKON D810 + Zeiss Milvus 135mm f/2

[low-res image for bot]

Conclusions

The “pop” or “3D rendering” or “brilliance” or “bite” of fine details that results from high micro contrast lends a feel to an image that many lenses lack. Check out the Zeiss lenses discussed in this article (and others) to get a sense of whether that visual impact changes the way you look at photography. What I often hear from readers of my blog with a first Zeiss lens is excitement at the look and feel of the images, which in large measure results from the contrast performance covered in this article.

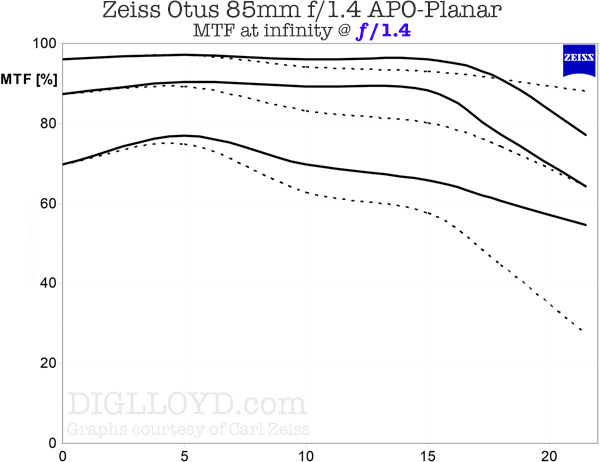

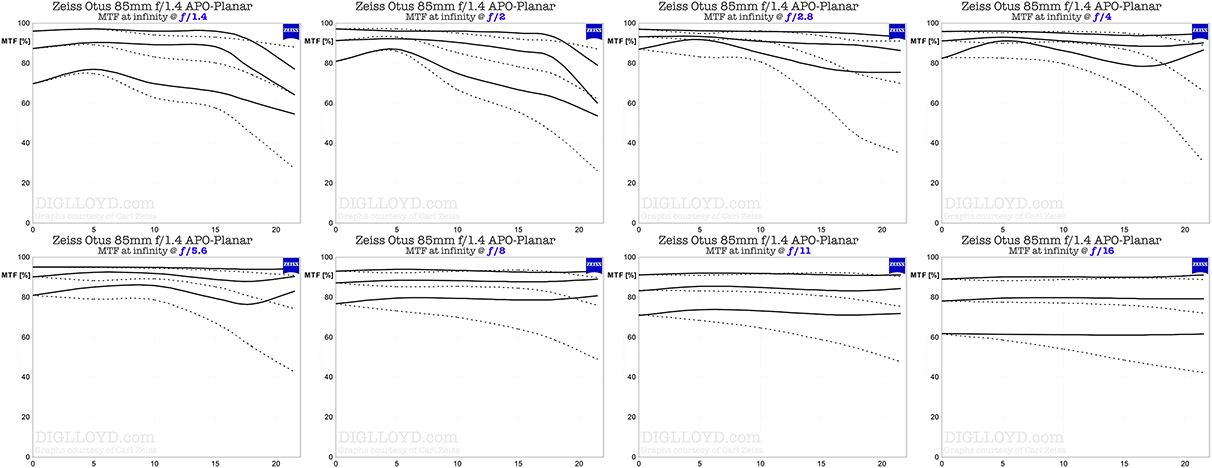

Addendum: measuring contrast, MTF charts

- Micro contrast refers to contrast of very fine details, such as 40 line pairs per millimeter (lp/mm). Modern sensors have resolution well over 100 lp/mm, so 40 lp/mm is a proxy for what happens with greater resolution.

- Overall contrast refers to contrast of coarse structures, generally taken as 10 lp/mm but also medium structures, generally taken as 20 lp/mm.

Contrast is typically presented using various types of MTF (Modulation Transfer Function) charts, though this article has focused exclusively on showing results from the field. At Zeiss a few years ago, I enjoyed a demonstration of the K8 MTF tester and saw just how variable results can be depending on how it is measured (including inserting the proper optical thickness of equivalent sensor cover glass for the camera platform), as well as how tiny changes in focus change the results.

Zeiss measures MTF with real lenses with white light, and thus the Zeiss MTF charts are based on the reality of built lenses and with diffraction in effect and with a full spectrum (not just green which bumps results up substantially). Zeiss MTF charts should not be equated to fantasy MTF charts that are computed best-possible-never-realizable in a real lens visuals, almost always without diffraction effects.

Shown below is a world-class performance for MTF (contrast) at 10 lp/mm (upper pair of lines), 20 lp/mm (next set of lines), and 40 lp/mm (lowest pair of lines). Contrast at this level at f/1.4 is rare among lenses. The pairs of lines are for sagittal vs tangential MTF. Observe that by f/2.8, contrast peaks, though f/4 makes for a more even performance across the field. At f/8, the contrast drops at all levels, this accelerates at f/11 and f/16 is inferior to f/1.4 for coarse, medium and fine structures. MTF of 75% and above for 40 lp/mm is what I consider world-class performance.

View the entire MTF series from f/1.4 - f/16.

Lloyd’s photography blog is found at diglloyd.com; it covers many brands, lenses, cameras. In-depth review coverage of the Zeiss DSLR lenses for Canon and Nikon is found in Guide to Zeiss DSLR Lenses. Topics like focus stacking are covered in detail in Making Sharp Images. By subscription.